Deconstructing Feedback

After studying the industry of game development over the past couple years I've come to understand something fundamental. Every game developer, from first-timers to seasoned veterans, are just as susceptible to the curse of scope. One aspect of this behemoth is knowing when to cut a feature and when to press on, especially in regard to how short of a time table game development typically is given. This affects even large businesses prominent through the unfinished games that have made it to shelves worldwide. As a result it is imperative for developers to understand when they need to pivot or plow on ahead.

In my first ever blog post, Game Development: The Student Restriction, I discussed just how little time student development projects have in comparison to full time studios. This results in a lower average level of quality coming out from game majors since there are a ton of other events constantly happening in a given week. Thus, it is more important for all student projects to get feedback on their idea early and often in comparison to their industry counterparts. This past week my team learned something about the core of our game's movement mechanic, but it took the weeks of testing to understand.

When we first challenged one of the major reasons we didn't pass was that we didn't have an answer for choosing a Squid as the player character. In hindsight we should have seen this coming from a mile away since the game was barely even a concept. We had a lot of ideas about where we'd go after completing the challenge, but in the process we didn't add any of them.So when we presented there was only the ability to breach a spaceship that had a decompression system. The results are plain to see in that we came across as not really understanding out own concept well enough to pass the first stage.

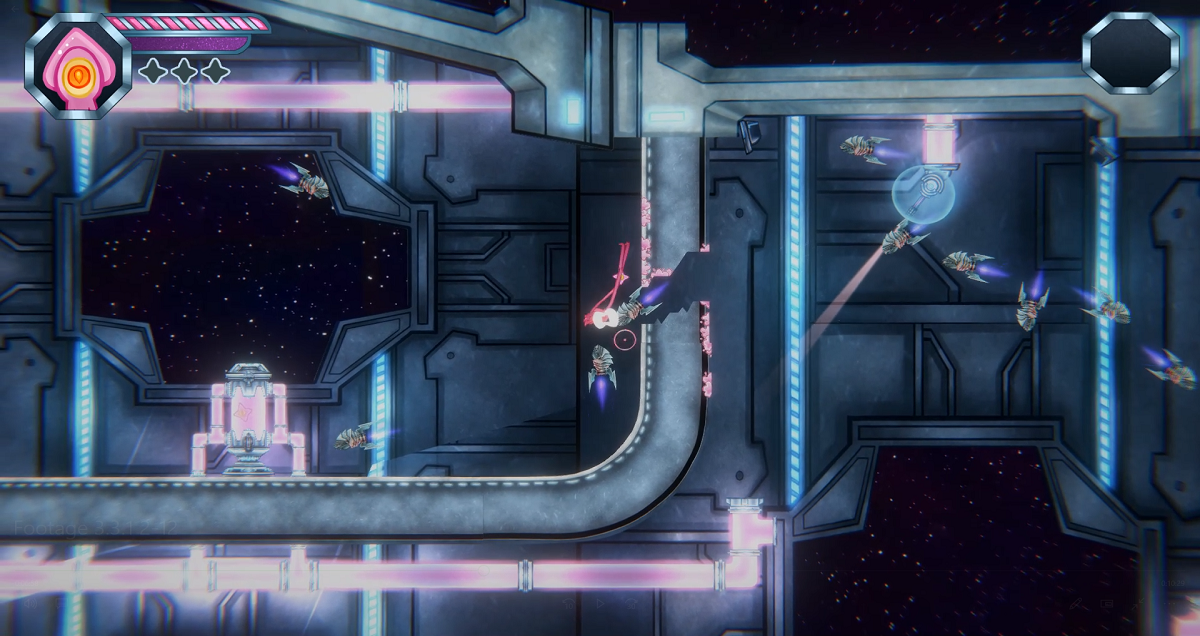

Following this we had a meeting where we started a now regular occurrence: set a Sprint goal. This goal allows us to properly plan that sprint and get the correct tasks within the sprint. After that failure we knew the first thing we needed to do was "increase squid by 150%," at least.We all agreed that for this we needed to add the tentacle ability that would be crucial for movement and combat. The idea here is that the player would be able to latch onto walls with the tentacles and swing around in gravity dodging the enemy to complete the objective. Our first iteration for this system was hard to use, broken, insanely buggy, and people hated it.

Now this is a crucial moment for any team where they need to decide: cut, pivot, or persevere on this feature? The key to figuring out this decision lies all within the feedback players give you. However, one needs to be mindful to understand that it is not only what they say but how they say it along with the context within which it is said. A huge component of this process is to understand where you are and where you want to be, and by extension those who can and can't see that vision. This early on it would be a mistake to listen to every tester that came across our game since it is so early in development. With this understanding we knew that we should take caution of taking the feedback at just face value.

One aspect that we understood needed to be fixed at face-value was the accuracy of the tentacles. In this early state they were heavily inconsistent in regard to what they would or wouldn't latch onto. Understanding just how far the tentacles go and how to properly use them took too long for someone to quickly pick up in a prototype level. So using the feedback of people's disdain towards the tentacles and our understanding of where we were at in development we prioritized making it easier to use. The real challenge came when we heavily improved the usability of the tentacles, but people still were slow and got frustrated by the mechanic.

Here I could have told the team that was our last opportunity to pull the plug on the mechanic. Testers weren't becoming attached to the idea in any capacity and it seemed like they never would. Maybe people just didn't want to be a squid in space. Yet instead of that we sat together as a team and brainstormed, even if we didn't know it at the time, of what to do to solve this issue.

We knew people didn't like the tentacles and could see by their play that many of them were barely even using them as well. Taking both the negative feedback and their play styles in hand we thought of a reason that might be the cause of both: they didn't know how to use them. With this mindset it became obvious that to really test if this mechanic had merit was to first make sure the player knew how to use the tentacles. To do this we created a short series of levels that ramped up in difficulty. The difference was immediately apparent after the first couple playthroughs.

People were slowly understanding what they could accomplish with the tentacles as they progress through the levels. At first they may have had trouble understanding even how to use them, but by the third level they were swinging themselves around the entire spaceship. The improvement also showed up in feedback with tentacles being the dominating favorite feedback for the first time. This showed us that this mechanic does have value to players while also providing them depth through mastery.

If this past testing session hadn't improved in regards to the tentacle feature I would be having a serious talk with the team. I can seem myself saying that the feature wasn't working, nobody was understanding it, and that we might want to focus on a different aspect. Now it has become cemented as a core part of both the movement and combat systems, but wasn't possible without testing.

We could have rejected player feedback as unintelligent and dismiss its validity. We could have talked back to testers who were playing our game they might not have given us honest answers. Through that we would have had a serious misunderstanding of what was important to the players, and maybe even had rejected the idea entirely. Instead of all that we thought long and hard about where the game was, what state it was in, and how that related to the feedback given. Understanding and accepting all of those things in tandem allowed us to make a better prototype before we even hit Stage 2 of Capstone.

I can't stress enough how important it is for student game developers to have this understanding early and to utilize it often throughout development. We have even less time that AAA studios who still have their games end up littered with bugs and incomplete areas. Don't be afraid to face feedback and try to process why players are reacting in that way. The fundamental design or direction of a game doesn't have to change because of feedback, but rather how you present it to the player. Now I don't want to say this is easy especially to developers who are passionate about their project. Many times they can become blind to simple, fast improvements they could have made if they only took the time to listen.

Thank you for reading, and I hope you test your games often!